51

|

50

|

Toolkit for Competition

Advocacy in ASEAN

Toolkit for Competition

Advocacy in ASEAN

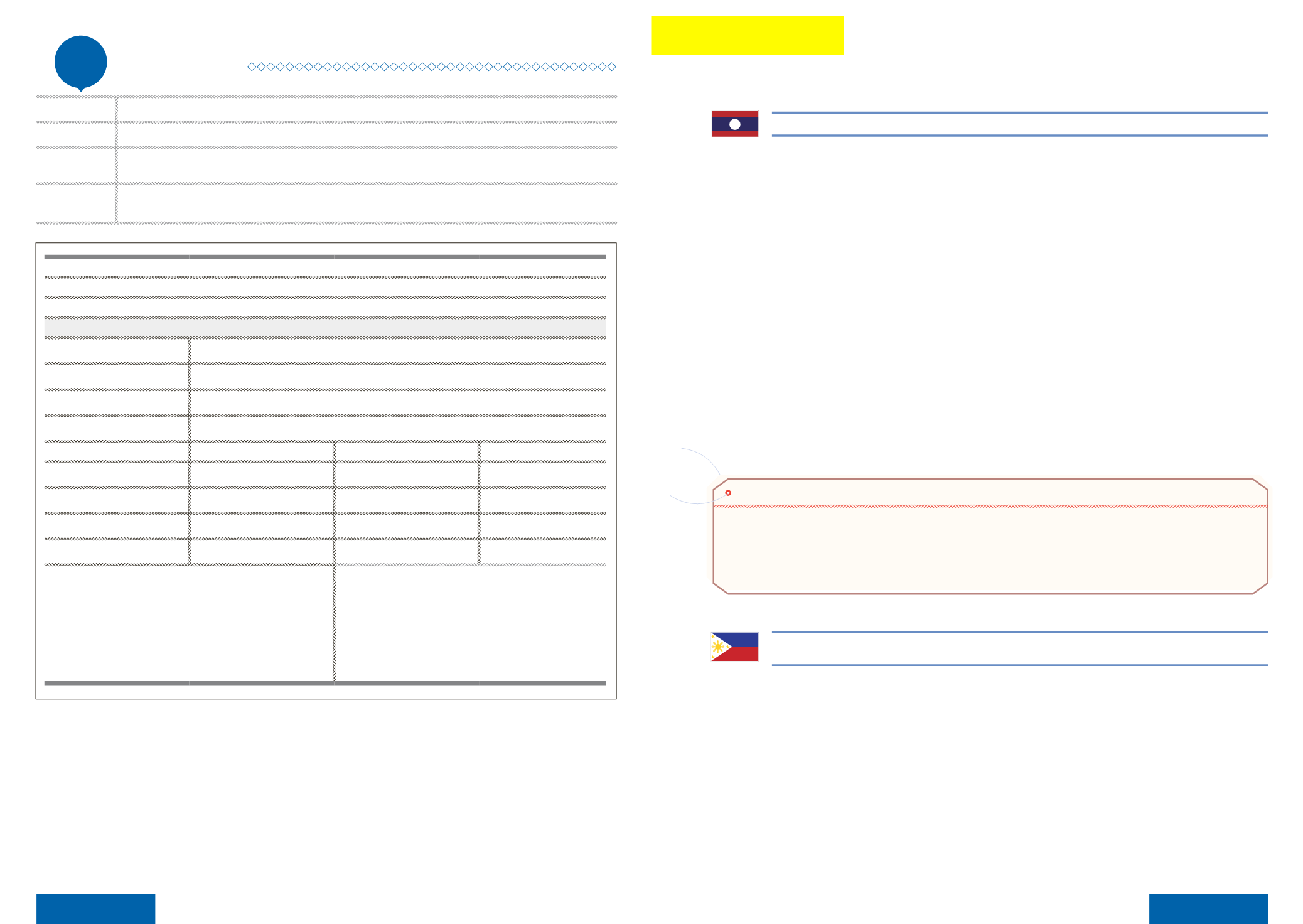

Feedback form

8

Purpose:

A management tool to evaluate an advocacy campaign and derive recommendations for possible follow-up action.

When to use it:

At the end of an advocacy campaign, or at a point when evaluation is required.

Setting:

Campaign director and/or project manager to ensure evaluation needs and requirements are available, organised or

requested.

Facilities and

materials:

-

Campaign Brief:

Campaign Objectives:

Campaign Duration:

Overview of Campaign

Campaign Sponsor:

Campaign Director:

Campaign Spokesperson:

Campaign Project Manager:

Campaign Working Group:

Methods and tools used

Budget and contractor

Set performance indicators

Campaign Sponsor

Campaign Director

Campaign Spokesperson

Campaign Project Manager

Evaluation data required:

e.g. digital, media analysis, focus groups, statistical reports, case

studies, etc.

PHILIPPINES: Towards a Unified Government Approach to Competition Reforms

in the Philippines

CASE STUDIES

Successful Approaches to Competition Advocacy in ASEAN

LAO PDR: Advocating for the Passage of a National Competition Law in Lao PDR

Take-Away Tips

Competition advocacy is a continuous endeavour and effort that is relevant already at the stage of drafting a competition legislation. This

is meant to garner and ensure the support of key stakeholders for the competition law from the very beginning, and to counter potential

adversity at a later stage by government agencies, legislators or businesses. In fact, competition advocacy continues to be crucial once the

law has been passed and CA set up, with some jurisdictions opting for a grace period to allow for businesses to familiarise themselves with

the provisions and implications of the law first. Drawing up a stakeholder map can direct advocacy activities in a more systematic manner,

but such map needs to be periodically reviewed in order to reflect changing dynamics and priorities.

In January 2016, the Law on Business Competition

of Lao PDR came into effect. In compliance with

commitments under the ASEAN Economic Community

(AEC) and national priorities, the law itself is the

product of an intensive consultative process that

involved multiple stakeholders throughout the various

drafting stages.

From the beginning, the

Ministry of Industry and

Commerce (MoIC)

set up an inter-ministerial drafting

committee to discuss the proposed provisions of

the new law. Over the course of several years,

representatives of additional ministries were invited

to attend the meetings on a regular basis and provide

their comments. This was done in the understanding

and realisation that the competition law has a bearing

on many other regulations and policies, such as

telecommunications or finance and procurement. In

parallel, sub-national consultation workshops were

carried out in selected provinces to raise the awareness

about competition issues.

Moreover, in cooperation with a local research institute,

the MoIC undertook a competition assessment,

Until the passage of the Philippine Competition Act in

July 2015, the Philippines followed a sectoral approach

to competition policy, with industry-specific laws

enforced by more than 60 regulators. This required

coherent policies across different agencies and

oversight procedures, in order to counter fragmented

enforcement and politicisation of the regulatory process.

With the creation of the Office for Competition

(OFC) under the Department of Justice in 2011, the

challenges inherent in the country’s sectoral approach

to competition policy were given due attention and

subsequently became part of the economic justice

agenda of the Philippine government. As the country’s

comprising a comprehensive mapping of key industries,

a legal inventory of competition-related regulations

and laws (e.g. on consumer protection), as well as a

perception survey among stakeholders.The competition

assessment serves to provide at least soft evidence

about the competition problems in the country, and as

such, is an important advocacy tool.

Learning from the experiences of more advanced

competition regimes, both within ASEAN and beyond,

has also been instrumental in the formulation of the Lao

competition law. In the final stages of drafting, a study

visit to Indonesia was organised for the MoIC together

with the responsible committees of the National

Assembly. The study visit was not only a good example

of an “ASEAN helps ASEAN” approach to enhance the

understanding about competition issues.

It also demonstrated the “fluidity” and flexibility of

stakeholder engagement and advocacy priorities during

different phases of introducing and implementing a

competition law. Advocating with legislators may only

be a priority from time to time, when there is a real

opportunity or momentum for regulatory reform.

first CA, the OFC recognised the power of advocacy

as complementary to enforcement and has been

proactively disseminating the benefits of competition

to the general public. In doing so, an emphasis was

placed on a number of sectors, namely energy,

telecommunications, transportation, and commodities.

This prioritisation was based on the assessment that

these sectors have the most impact on consumers.

The sector-specific advocacy of the OFC has brought

about important insights into specific industries. In

the commodities sector, for example, an investigative

report showed that the rise on the prices of garlic and

onion was not caused by a shortage in supply, but due